Black Canadian History with Irene Moore davis

TWO BLACK GIRLS TALK ABOUT EVERYTHING PODCAST: EPISODE 5

Show Notes

Rate, Review and Subscribe on Apple Podcasts

“I love Dianne, Dee and the ”Two Black Girls Talk About Everything Podcast.”

Please review the podcast, then be sure to let me know what you loved most about the episode. Also, if you haven’t done so already, subscribe so you get notified every time a new episode is available!

Transcript

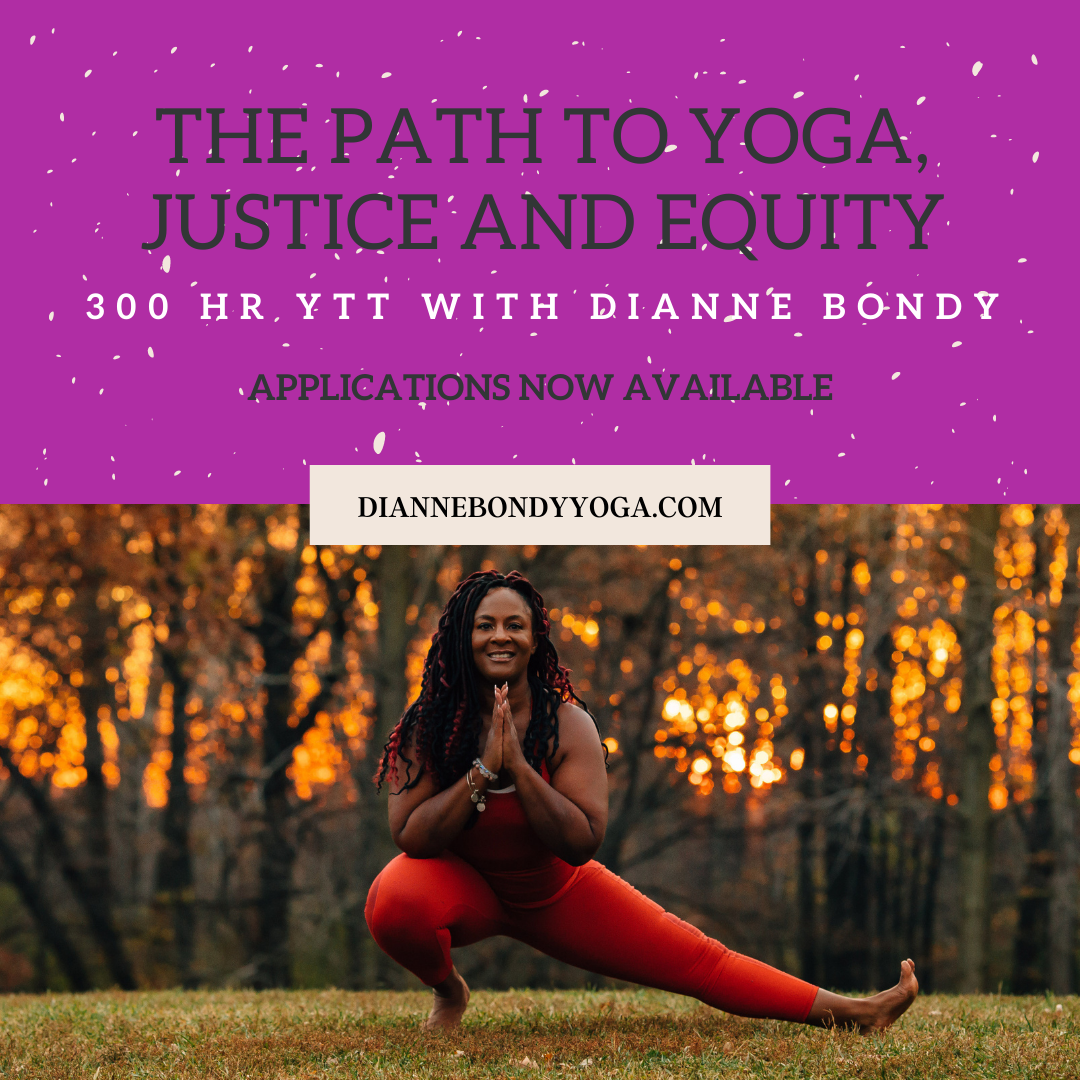

More Ways to Study With Dianne

Dianne: (00:12)

Welcome to the Two Black Girls Talk About Everything podcast. I’m Dianne.

Dee: (00:16)

And I’m Dee, and we’re going to be talking about everything.

Dianne: (00:19)

We’re going to talk about yoga and fashion and-

Dee: (00:22)

Just-

Dianne: (00:22)

Everything Black girls talk about.

Dee: (00:24)

In today’s episode, we’re going to be talking to Irene Moore Davis, author, educator, and historian on what Black History Month means in Canada. Black History Month here in February is a global phenomenon, but often our history in Canada gets overshadowed by the accomplishments of African Americans. We want to celebrate what it means to be Black in Canada. So listening to the podcast, as we look at our history, our collective history on the border with Detroit and what it means to be black in Canada.

Dianne: (01:01)

Irene Moore Davis is an educator historian, author, and activist who speaks and writes frequently about diversity inclusion, and African Canadian history. She fulfils a variety of community roles including President of the Essex County Black Historical Research Society, Programming Chair for Book Best Windsor, co-host of the All Right in Sin City podcast, co-chair of the Black Women of Forward Action, member of the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force of Windsor Ethics, and member of the Anglican Church of Canada National Dismantling Racism Task Force. Irene’s publications have included poetry, history, and journalism. She’s a graduate of the university of Windsor, Western University, and Queens University, and is an administrator at St. Claire College where she also teaches English, underground railroad history, and Black cultural studies. Welcome to the podcast, Irene,

Irene: (02:03)

Thanks for having me.

Dianne: (02:04)

Welcome, Irene.

Irene: (02:05)

Thank you.

Dianne: (02:07)

Like I was saying before we started recording, I have been so excited to talk to you and my excitement has been increasing one, because it’s Black history month right now and we very rarely see Black Canadian history centered in our conversations in Canada. We seem to pivot on African American history. Our histories are uniquely joined and very interesting but we never seem to bridge that divide between the two countries. Because we live here in Essex County, literally minutes from Downtown Detroit, we have this incredible experience that not only is Canadian history and American history, but world history. The links from the continent of Africa all the way to the continent of North America, and all the things that in between.

Dianne: (03:00)

My interest in Canadian history peaked when D&I reconnected. We’ve been friends for years, everybody knows Dee in the City. Dee has a very robust history in this area and when we started training for our free press half marathon this summer, I got to learn so much more about Canadian history through her lens, through her eyes, through her experience. I think it’s so powerful to share those stories, those oral history stories. We were recently talking about how little we know about Canadian history. My first taste of it is when I opened my first bank account, there was a teller at the bank who was Black.

Dianne: (03:42)

I assumed because everybody I had known in my circles had been from the West Indies — my mother had a group of friends from who were all over the West Indies and they kind of raised their kids together — so I just assumed all Black people were from the West Indies. I think I’m 11 at this point, right? I’m talking to this teller and she’s like, “Oh no, I’m from Nova Scotia,” and I’m like, ” There are Black people in Nova Scotia?” The look of horror on her face to say, “You don’t know about the Black people in Nova Scotia?” I’m like, “I don’t know about the bBack people in Nova Scotia.” I’m 11 years old. Shouldn’t this be part of my history teaching? Why do we not elevate or talk about Black Canadian history, especially in, I think, a really incredibly historical place in Ontario.

Irene: (04:31)

It a fantastic question. It was a good preamble though. It’s so characteristic of the experience that people have going through the school system here in Ontario, that they just don’t learn that, so that even you, as a proud, informed, intelligent young woman of African descent did not have a sense of that African North American history, right? We’re working on it.I would say that there has been a long standing reluctance to focus on anything in Canadian history other than the history of the dominant peoples, and not even all people of European descent. We do so little work in the average K to 12 history class or social studies class even on non-English, non-French White history, right?

Irene: (05:19)

But to focus on Black history, yes, Canada played such a pivotal role in the underground railroad, obviously. This was the main terminus of the underground railroad. We have all of these incredible stories right here in Southwestern Ontario, where we’re recording this. It’s just so unfortunate that it’s not told but I think part of that is just that teachers are not sufficiently well-educated about that history and don’t have the confidence to share it in a knowledgeable fashion, and also just the fact that it’s never been mandated as part of the Ontario curriculum. Teachers have a tendency to default to things that they are required to cover, of course, and so while we have some real initiative taking educators around the system that are making use of materials and trying to bring them into the classroom, it really is dependent on the individual initiative of the teacher to do that. Many of them just don’t feel comfortable, don’t feel they have the time.

Irene: (06:17)

We’re working with, with school boards to develop more materials and update the materials that they have, and make sure that teachers do you feel comfortable covering it. For example, right now I’m on a committee that’s working with the greater Essex County District School Board to update their African Canadian Roads to Freedom resource materials which have been available for years for teachers to use, to introduce black history into their classrooms, but often don’t get used because people just don’t feel that they have the confidence to do it. They don’t feel that they know enough. They’re scared of saying the wrong thing. They’re scared of bringing up issues of race without the training and the competence to do so.

Irene: (06:59)

There’s this tendency, even during things like Black history month, to default to whatever they can find on the web, which very often is content about Rosa parks and Martin Luther King Jr and all of that great stuff which tends to be American in focus. We’ve got a lot of work to do but I’m so pleased that the Ontario Black History Society is taking the lead here in Ontario, at least, in terms of their Black history campaign and trying to encourage members of the public and organizations both within the Black community and outside of it to write to the Minister of Education, write to the Rremier, lobby for black history to be more included. Surely it’s time.

Dianne: (07:42)

You know, Black history is our history. It’s a collective history. I’m going to be bold and say this, nothing in the world hasn’t been touched by a person of African descent. Nothing. Our legacy has led to the building of North America, to the building of Europe, to the building of this entire world. Indigenous people, whether you’re indigenous to Australia or New Zealand which has a dark skin or a Black skin indigenous population, whether you’re from the continent, we touch every part of the world yet our history is denied to us. It’s 2021 and I often go up to my kids and go, “Okay, I want to know what you’re learning about your local history.” Because my children are born here. My husband who is White, his family were the first settlers that were here so their history intwined in this as well as it’s intwined in Barbados and the Transatlantic slave trade that brought my family to Barbados, right? It’s all intertwined And I think it should be a global undertaking. i really think that recognizing black history one month out of the year is a huge disservice to humanity.

Irene: (09:02)

I think that it’s a case of baby steps needing to be taken. I totally understand why in 1926, Carter Woodson felt that it was necessary to have a Negro history week, which was the terminology of the time, and I understand why over the decades there was a push to have a Black history month. I think that we’re in a phase where we still need an opportunity to highlight our history but I happen to believe that we can do that all year round, and we should. Honestly, what you say is so correct. People of African descent have touched every culture. What is more exported or imported or traded than hip hop culture, for example? It is a global phenomenon, right? People have been using our music and our postures, our fashions, our styles, all of those things, for decades if not longer.

Irene: (09:57)

There’s also simultaneously this great confusion that exists over the state of race relations, the situations in which Black populations around the world find themselves, and that would be so much easier for people to understand if they had any sense of history. If they had a sense of the Transatlantic slave trade, if they had a sense of how colonialism interrupted or disrupted Africa. We have this tendency to look at how things are now without understanding how they came to be. If we want to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past, we’ve got to learn from the past, right? It makes sense on all kinds of levels,for all kinds of people to learn Black history, not just kids of African descent, but everybody,

Dianne: (10:39)

It is our collective history and we have so much to learn. I’m always excited when February rolls around, because I always learn something that I had no idea about. I was talking to my friends and I said, “Prominent Black Canadians that I knew about were Lincoln Alexander because I grew up in Burlington and we drove down the Lincoln Alexander Parkway.” That was important that when we were on it, that my parents were like, “Do you know who this is named after? Do you know why this is important?” Things like Oscar Peterson. That was my first prominent Canadian where I’m like, “He’s Black and he’s going to get the order of Canada.

Dianne: (11:16)

All these things that I completely missed out on that made me so sad, that has made it a priority for me to teach my children, and for me also to dive back into my own Caribbean history and culture and learn about all of that, because it’s all intertwined, and then it’s intertwined with like our colonial history. I had no idea. Two things I learned, one I learned from Dee, I had no idea that slavery existed in Canada. Not to the extent that it existed in America and not with forced breeding that they had in America, but still it was present here around the time of the British North American act. Slavery was a thing here. I don’t think people understand that, and I think Canadians constantly break their arm patting themselves on the back for not being slave owners and Americans.

Irene: (12:14)

Yeah. I’m going to make a slight revision to what you just said. At the time of the BNA act it was over but I will say yes, slavery existed in Canada. Slavery existed right here in Windsor where we’re sitting, right here in Essex County. Tons of it. We did not have a plantation based economy because we don’t have the climate or the crops for that sort of thing but we certainly had slavery all over, both the French colonists and the United Empire Loyalists who were loyal to Britain had enslaved people. We’ve got a city full of street names that reflect slave owning families. That’s a whole conversation that’s going on about how to address that reality. The Bobbies, the Duffs, the Elliots, all kinds of people, [Labidys 00:13:00], Askins, owned enslaved people both of indigenous and African heritage.

Irene: (13:07)

It was incredible to a lot of people to learn over the last couple of years that that was the case because we have a tendency in Canada to see ourselves in contrast to the United States. It’s a really simple narrative, an overly simplified narrative that we all adopt from the time we’re children that we’re the good ones and America’s bad. That’s the way that our history is taught to us in school so complications are left out of the picture because they are not conducive to that pretty tidy narrative and we don’t want to think of ourselves in that light. We like to think of our history of African presence starting with the underground railroad when that was not the case.

Irene: (13:49)

In fact, there were people crossing into freedom in upper Canada due to complications of the legal system who were finding themselves in freedom here and living in cities where there were still enslaved people leftover from before. Our act to limit slavery and upper Canada in what’s now Ontario only mandated that people be freed from slavery if they were under 21, otherwise they were enslaved until the end of their lives or until their owners decided not to keep holding onto them anymore, and that was often because they didn’t want to have to keep taking care of them. Then you’ve got this other problem, right? Even as the underground railroad was starting here, there were still enslaved people walking around and living in Windsor and other parts of Essex County.

Irene: (14:36)

We know that Matthew Elliot out in Amherstburg had 60 enslaved people on his property. A lot of them, he had picked up in raids during the American revolution and just seized them as enemy property and took them home and kept them. We have to be aware of that. Every time I’m taking a pretty ride down the river towards Amherstburg and I go past Elliot Point, I think about those enslaved people. I think there are folks living in those lovely houses that have no idea that that went on there, on the property that they’re occupying. we have a lot to learn for sure.

Irene: (15:11)

While that’s a sad story, I’m trying to recognize those enslaved people. I’m working with the city of Windsor on getting some signage for those streets that are named after slave-owning families not to bash the families per se or their descendants. That’s not the goal. The goal is to recognize the work that these individuals did. I don’t think that a lot of people around our area even know that there were people of African descent who were clearing this land and making the settlements possible in the first place, and working in the fur trade and doing all of this farming before the era of the underground railroad.

Dianne: (15:50)

You know,what blew my mind that I recently learned because this has been my project? I’m taking a course at Queens University — you can take it free online — learning indigenous history and black history. This is a course you can take. My husband laughs at me. He goes, “With all your free time.” I said, “Instead of like watching YouTube and TikToK I just listened to these lectures, one thing I had no idea about and Dee, you can chime in on this if you knew, that there was a trade route from the continent of Africa to North America before the Transatlantic slave trade. What? I was many years old when I learned this.

Dianne: (16:32)

I think I learned this last month and that blew my mind that our African descendants and the indigenous people of North America were already trading with each other. Some people would stay here and some people would go back to the continent and we have been intermingling forever. that to me was just like, “We are so brilliant to figure these things out on our own, and we don’t ever get any credit for that.” You see how excited I am? I was just like, “Wow!” Again, I was this many years old when I learned this. I learned this last month. That blew my mind that we don’t know about these things.

Irene: (17:11)

I was very fortunate to read all of the books of Ivan van Sertima when I was in university. They weren’t part of my university curriculum. They were just things that I enjoyed reading. When I was in my early twenties, we actually brought him to Windsor to speak at the Amherstburg Freedom Museum’s annual banquet. That was just such an eye-opening and beautiful experience that I’ll never forget. I found that out by accident because some relatives recommended some books for me. These are things that people should learn in school. They should actually learn in school.

Irene: (17:39)

We look at the curriculum in terms of exploration and what students are learning even in 2021 in elementary school, they’re hearing about the European explorers, they’re hearing about Vikings maybe, but they’re not learning anything about the trade routes of racialized people or indigenous people. They’re not even hearing about Matthew de Costa, who was the first Black man on record to arrive in Canada back in the 1600s and came with the European explorers as a navigator; a Black man who grew up in Portugal. It’s so unusual and a little disappointing that that information is still kept so secret and it should be shared with students. That’s exciting. For one thing, it’s just a great story. If you want to arouse the excitement and the passion for learning among students, you would think you would want to build some of those elements in. It’s just so much more interesting than, “These White guys all showed up.”

Dee: (18:47)

I find too, when I think when back to being in school, if it hadn’t been for my family having such a strong storyline and my dad was very adamant about passing these stories down, and then working at the museum all those years, the things I learned in school, they did touch on these things but the things that were taught were very biased, and I wouldn’t have known the difference. I don’t know what’s worse, not teach it or teach something that’s biased.

Irene: (19:16)

Yes, I understand that, and that’s one reason why it is important that teachers be given some training to go along with this information. That’s something that I know the Winsor Essex Catholic District School Board is working on right now. Navigating how to provide appropriate training to teachers rather than handing them a bunch of material or referring them to the vetted stuff on the website and saying, “Incorporate this into your lessons.” If it’s delivered in a way that’s patronizing, if it’s delivered in a way that still does not have inclusive language, if it’s delivered in a way, that’s like, “Okay, we got to throw this in,” it makes things worse. We want every child to just love this history whether they are of African heritage or not and just to see how exciting it is, especially the history of this area. I hear from people at the college level all the time not only that they didn’t learn any Black history the whole time they were in K to 12 but they didn’t even learn any local history. What a shame that is.

Dee: (20:20)

I remember being in school and having a teacher touching on Black history and me saying to my teacher, “My dad went to a segregated school here in Essex County, which was Herro.” I believe it was one of the last ones that existed but he went to it until grade five and the teacher completely denied it. He pointed at me he’s like, “That didn’t happen. That didn’t happen.” I’m like, “It did happen.”

Irene: (20:48)

SS number 11 is a story that needs to be told as well because aside from the oppression that that’s part of that story obviously, keeping these young kids of African descent at this school that didn’t have indoor plumbing, that had wind blowing through the walls and they had to go out and chop wood for the stove like in the 1960s, ridiculou, and the opposition and resistance to letting them come to the, to the school that the White kids were attending. Friends of my family also attended that school and one person that I love very much, she’s always been a mentor in my life ,was one of the last Black teachers at that school. One of the last teachers.

Irene: (21:29)

Aside from that story of oppression, there’s also the great story of how the Black citizens of South Essex rose up, got together, formed an organization, weren’t getting any cooperation from the local school authorities so they went national. They got Leonard Braithwaite involved, speaking of Barbados. They reached out to the media, the Toronto Star was down here covering the story. That’s how they got it done and that’s a beautiful story in itself.

Dianne: (21:57)

Absolutely.

Dee: (21:58)

I grew up really hearing a lot of the stories for my grandparents about what went on in those meetings and the fight that they had.

Dee: (22:07)

That’s so incredible. That’s what I learned about Dee this summer, is that schools were segregated. Dee’s dad is like 11 years older than me. That is how recent this history is. I think when we talk about Black history and when we talk about enslavement and when we talk about all those things, we talk about this like it’s something that’s far in the past and it is so not. I’m 50. I’m going to be 51 in a couple of months. Dee, your dad’s like 61 or 62, right? Somewhere in there?

Dee: (22:39)

He’s 63. Yeah.

Dianne: (22:41)

63, and he went through a segregated school. That’s just mind blowing. There’s only 10 years between us and that has happened right here on Canadian soil that we don’t even hear about or we don’t even know about. I think it’s sad.

Irene: (22:56)

It is said. We do need to hear those stories and everybody needs to know those stories. It’s unfortunate that anyone in the education system, a teacher, was denying that story.

Dee: (23:09)

Oh yeah. Yeah. It didn’t happen. I don’t know if it was a defense thing or he didn’t know for a fact so it was better off it didn’t happen. I’m not quite sure.

Irene: (23:28)

Incredible.

Dianne: (23:30)

We don’t want to believe we’re bad as Canadians, right?

Dee: (23:34)

Like what Irene was saying. We always want to see each other in a better light. We don’t have it as bad as the States. Yeah.

Irene: (23:46)

Black History is a great way to get all of us to question our privilege too, and I mean,all of us. It’s a great discussion starter, conversation starter, because it also leads us to ask questions about the injustices that are going on right now. When we want to see ourselves as the heroes, we deny ourselves the opportunity to really ask questions about how we can be better. I think if we want to really solve these issues, we’ve got to dig back into the past and do the work to discover how we came to be this way, how these systems came into being, how it is that we’ve got these problems of over-representation of certain people in the criminal justice system and child protective systems, the wealth gaps and all of those things. We’ve got to take a look at that: an honest candid look.

Dianne: (24:41)

That happens here. I hear about it. I do a lot of work in the States. People are always surprised to hear that I’m Canadian until I say out and about and then they’re like, “Oh, wait, you are Canadian.” I had a couple of friends say to me, “You live in Windsor, you’re barely Canadian.” I go, “I’m still Canadian.” I think a lot of our Canadian identity is focused on not being American. We need to have a stronger sense of identity. In the 12th grade, we had to read an essay about finding the Canadian identity and the essay was called Finding the Canadian Identity is Like Trying to Find a Needle in a Haystack. We are so overwhelmed by our neighbor in Windsor Essex County to the North of us, interesting geographical fact, but we are so inundated by that culture that the lines get blurred for us.

Dianne: (25:38)

I think they would be less blurred for us if we were more steeped in our own history. If we weren’t so overwhelmed by — I like to think of it as American centrism. America needs to be the middle of everywhere and it needs to be influencing everything. I just think Canada needs to take more stock in itself and the positive aspects. The way people rose up. The way change happens. Because what I have noticed is consistent, whether you’re an African-American or a Caribbean Canadian — that’s how I call myself a Caribbean Canadian — or a Canadian of African descent, what I find the theme that happens with all of us is that we rise up. We are good at organizing. We are good at figuring things out and we are good at speaking up. I think that really should be highlighted when we’re talking about our history.

Irene: (26:33)

Necessity is the mother of invention. Honestly, so many people have benefited from our rising up over the years. Our demands for equal rights have created pathways for other people to have them. I certainly think one of the best examples here in Canada is that group of primarily Caribbean Canadians but also some African Canadians who went repeatedly to the federal government to get them to overturn the unjust immigration systems. Now everybody rides that wave into Canada on the backs of this work that was done over many years by people of African descent in this country to get rid of those negative built in unjust systems that made it easier for European descended people to get here and not racialized people. The systems of codes and assigning extra weight to certain countries and so on. When that immigration overhaul happened, it benefited a lot of different people who are now a great part of this nation. We’ve got a lot of great stories to tell and I think our history is just as interesting as American history. We just have to do a little bit better job of telling it and being willing to hear it.

Dianne: (27:49)

100%. A quote that I listened to all your CBC interviews and when I was researching for this podcast, and I love that there wasn’t an artist or an activist in Toronto that was putting up additional plaques on streets that were named after people who had enslaved Africans. I loved the quote that she put up. It said, “What we accept, what we honor and what we choose to honor says a lot about what we value as a society.” That’s your quote. I wanted to start the podcast with that. I just got so excited seeing you. I just think that’s an amazing way to look at the world. Who we choose to honor tells us a lot about who we are and it also tells us, it also tells the people that we don’t honor that they’re not valid, and that’s really hard.

Irene: (28:46)

Yes. I mean, there is a great conversation that’s happening all over the world, really in terms of who should be on the monuments? Who should be on these statues? Who should these street names and place names and buildings being named after? I’m so thrilled that there’s better progress being made to open up the conversation about who should be honored. Especially in a community as ethno-culturally diverse as ours is, it makes so much sense to make sure that we don’t just have parks and streets and things that are named after affluent White guys.

Irene: (29:21)

The renaming of the park next to Mackenzie Hall earlier this week after Mary Miles Bibb was such a joy. That’s absolutely thrilling. For those who don’t know, Mary Miles Bibb was an African-American born in Rhode Island, who was part of the anti-slavery movement. She married Henry Bibb who was a formerly enslaved person himself, and who was also a noted abolitionists. They moved to Windsor in 1850 — to Sandwich actually.– and they started The Voice of the Fugitive newspaper. She opened up a school for Black children and adults. She did all of this stuff.

Irene: (29:31)

She also had a dressmaking shop, kind of fabulous. Started a literary society, helped to run the Refugee Home Society which provided opportunities to purchase discounted lands to formerly enslaved people so they can finally have their own farms. She did all this stuff. She’s been a person of national historic significance in Canada since 2005 and there was a federal historic plaque about her and Henry over on Sandwich. Finally, the City of Windsor decided to name that park, Mary Miles Bibb Park, and that’s largely through the efforts of TJ Travis.

Irene: (30:34)

It happened this week just on Tuesda and it’s so thrilling. We need more of that. In October, the University of Windsor will be unveiling, a life-size bronze monuments of Mary Anne Shadd Cary at the Downtown Campus. We’re looking forward to that. We need more of that in this city and we need more of that everywhere, and not just. Even though I represent cultures of African descent, it’s not even just about cultures of African descent. We need more things named after women. We need more things named after the queer community. We need more things named after indigenous people. We need more.

Dianne: (31:09)

All of it. All of it. I think the days of holding up a lot of accidental explorers who stumbled across a country that was already here and that was already thriving before they showed up, I think those days have come to an end. I think we really need to tell the truth of history. We always talk about history from the perspective of the victors. It’s really important now to flip the script. You’ve had all this time to marinate and what your history is. It’s now mine to give other people an opportunity to share their history because once again, it’s a collective history. I’ve been so grateful to reconnect with Dee because she has educated me. When we were training for that marathon there was a lot of running. It was really great to hear her tell her stories about working at the Black museum and telling me about what these local people like, “You don’t know, these people owned slavery? You don’t know this happened here? I’m just so grateful to learn about this because this is also part of my children’s history,, right?

Irene: (32:13)

Absolutely. First of all, I just want to express my amazement and respect for people that can actually hold conversation while they’re running. If I’m running, my conversation is — I’m not telling anybody anything other than, “Water.” Wow.

Dianne: (32:38)

Dee can talk. I would just let her talk about history so [crosstalk 00:32:42]. I’m learning stuff that I didn’t know. rene, what is your suggestion for educating ourselves? Right now, as we work towards getting this education in the school system, how can parents educate their children in this subject?

Irene: (33:07)

I think that’s a beautiful, beautiful question. We do have to educate ourselves. We have to be able to go and talk knowledgeably to teachers and administrators through Zoom or Microsoft Teams or whatever, but we have to be able to have the confidence that we know what we’re talking about too when we’re making these demands and requests. Right? We have to do some work at home to fill in the gaps, unfortunately, in what our kids are learning. The greater Essex County District School Board has an amazing resource. Several of us worked on it in the community, along with their educators. It’s called African Canadian Roads to Freedom. It’s available to the public right on their website. If you go to publicboard.ca I believe, and look for resources, you’ll find African Canadian Roads to Freedom.

Irene: (33:52)

That’s a great document that has information suitable for every grade, that’s about Black history. It’s national history as well as local history from this region. There are a lot of great websites. Definitely look to the Canadian Heritage Black history resources, the resources available through the Archives of Ontario on Black history are fantastic. The Ontario Black History society has great online resources. Historica Canada has some great resources, many of which were developed by Natasha Henry who’s not only a friend but President of the Ontario Black History Society.

Irene: (34:27)

There’s a lot of excellent material out there. Be cautious about homemade websites. A lot of people want to do their own tribute page to Black history and there’s a lot of great intent and inaccurate information so we want to be careful with that. We want to make sure that what our kids are learning is true and accurate and appropriately cited, researched, all that, so do keep an eye on that. Just as one example, one of my favorite people to talk about in Essex County history is the amazing Delos Rogest Davis, an incredible man. Do I have time to tell his story in like a minute or something?

Dianne: (35:04)

Yeah. Go.

Irene: (35:06)

Delos Rogest Davis came to Essex County with his parents on the underground railroad. So they make this incredible journey from Maryland to — I think they landed in Amherstburg and then ended up in Colchester Delos Rogest Davis had no opportunity for education until he got here. Obviously, he was living in slavery. He becomes this really brilliant student because when you give people a chance to be educated, it’s amazing what you can find out about their skills and their competencies. He became a teacher and then after a while he decided he wanted to be a lawyer. He studied law. In those days, they didn’t really have faculties of law, per se. You’ve got your law books, you studied under someone’s tutillage and then you have to do an articling placement so that you can get some experience and write the bar.

Irene: (35:55)

So he tried and tried and could not find any lawyer to take him on as an articling student because of racism. Eventually, he went to his member of provincial parliament and asked him for help. The Ontario government actually passed a law allowing Delos Rogest Davis to write the bar without having had any articling placement. He passed the bar and he became one of the most successful lawyers around. When I spend time going through old newspaper articles from the late 19th and early 20th century, Delos Rogest Davis is all over the place. He was a superstar. He had offices in Amherstburg and Windsor. He handled all kinds of trials, and he became the first person of African descent in the entire British empire to receive the King’s Counsel designation or what we would Queen Counsel now.

Irene: (36:46)

My goodness, he was born in slavery. He came here at the age of something like 11. He did all this. This is just one great example of what can happen when somebody is given the opportunity or at least has the opportunity to seize, right? This is the point I’m getting too. Often it’s the case that on different websites, they’ll say, “He was the first Black lawyer in Canada.” No, he wasn’t. He was the third Black lawyer in Canada. There was Robert Sutherland, Queens graduate, who was the first Black lawyer. He was Jamaican born and he actually left his fortune to Queens and saved them from bankruptcy upon his death because he just loved Queens so much and he’d always been treated like a gentlemen there. He also had no next of kin. Then there was Abraham Beverly Walker out in New Brunswick. Black loyalists, second generation person who became the first Black lawyer in New Brunswick. Then there was Delos Rogest Davis.

Irene: (37:43)

That’s not taking anything away from Delos Rogers Davis. He is the first underground railroad traveler’s become a lawyer. My goodness, what more can you ask of anybody? It’s an incredible story, but not the first Black Canadian lawyer. Tat’s what I mean. You can Google him and you’ll find seven, eight different websites that say he’s the first Black Canadian lawyer. We do have to guard against that stuff, that kind of inaccuracy, because then it detracts from all of the great truths that are out there. Another example that I think of, you’ll find all kinds of information about Elijah McCoy, one of the greatest inventors, not only Black inventors but one of the greatest inventors in North American history. You’ll find a lot of American websites saying, “He was from Detroit.”

Irene: (38:27)

Not really. He was born in Colchester. He went to school here. He became a mechanical engineer but could not find a job as an engineer because he was born in 1843 so you can picture there weren’t a lot of engineering jobs for Black people back then. I mean, heck we still have lots of Black engineers driving cabs and stuff right now. But in fact, he had to get a job with the Michigan Central Railway just doing manual labor, despite all of his skills, his expertise. But he was noticing how inefficient the trains were and how how easy it was for people to be injured just having to manually lubricate these engines. These engines would seize up and they’d have to stop the train, someone would have to go lubricate them. Very easy to be burned and so on.

Irene: (39:14)

He developed, on his own time, in his own workshop, the lubrication cup which automatically lubricated the train’s engine as it kept going, and that revolutionized the industry. That was the first of his 57 patented inventions. People like to say, “Greatest African-American inventor.” Yes, he did end up in the States but he was from here. He’s one of my favorite Essex County stories. That’s the kind of thing people should be learning in school. It’s about science. It’s about math. It’s about history. It’s about, you can do anything. He was born to formerly enslaved people from Kentucky who had moved here on the underground railroad. These are the kinds of stories we need to hear.

Dianne: (39:56)

Absolutely. I’m so proud when I hear these stories. I’m so proud to tell my children these stories and it informs who they are. It gives them the opportunity for greatness because I really and truly believe in that. That old adage or that colloquialism that you cannot be what you do not see. Somehow, as African descendants, we still become things we don’t see in our own communities, which speaks to the power of who we are when we are given an opportunity and a chance. That has reverence and that feeds my soul to know that we can come from so little and gain so much even under the oppression of White supremacy because all of this is happening in a White supremacist society, right? It’s not like all of a sudden slavery is over and everything’s equal. In 2021, we are still fighting against White supremacy and people still rise and people still do well, and families still thrive, even though we are constantly pushing back against the delusion of White supremacy.

Irene: (41:16)

We have so many stories like that, just these amazing stories of overcoming. You can focus on the oppressive aspects because those are definitely there. People had to overcome something, but I love just to share these stories of what people did about it. Even those that aren’t famous. I just think about these underground railroad travelers who came here in the mid 19th century and wanted to send their children to school and discovered that the schools were barred to them. That there was racism, that there was segregation, that they weren’t allowing black children into the schools, in the public schools in this County.

Irene: (41:55)

Who had just come out of slavery, but who are dictating letters and getting hold of their members of parliament and writing to the Minister of Education, Egerton Ryerson, and all that stuff, and using the courts for lawsuits. Pooling their resources and suing. That’s incredible to me. This first generation of people who came here, they had a dream of freedom. They knew what it meant to them and when they saw how things were, they didn’t just sit back and say, “Oh, well, that’s too bad.” They were working on it. Honestly, their energy fuels me a lot of the time because with all the advantages and privileges that we have, there’s no reason why we should just take things lying down.

Dianne: (42:41)

100%.

Dee: (42:41)

Irene. Sorry, go ahead.

Dianne: (42:41)

Go ahead. Go ahead. I talk a lot. Go ahead.

Dee: (42:47)

Irene, I was going to ask you, besides the resources that you gave us that families can learn online, once this whole COVID thing — hopefully soon — starts to pedal out, where are some in-person resources, some places that we can visit? I know you were talking about all the different streets and all these landmarks. Something that families can go out and do in order to educate themselves as well in-person.

Irene: (43:16)

Absolutely. I mean, first of all, what I want to say first is even during the pandemic, a lot of the local historic sites and museums have virtual tours available so check out on the John and Jane Freeman Wells historic site, the Amherstburg Freedom Museum, the Buxton National Historic Site and Museum, the uncle Tom’s cabin which is run by the Ontario heritage trust. All of those places, check them out and make maximum use of the virtual opportunities to learn. Beyond that, we have the beautiful Tower of Freedom Monument on Pitt Street that I think every family should go and look at it. It’s not just that it’s a beautiful statue by Ed Dwight. It’s been there since October 20th, 2001 so it’s the 20th anniversary coming up, but it’s also got the National Canadian historic plaque about the underground railroad. It’s here in Windsor for a reason because this was such an important place but it’s also got information along the sides of it at the base.

Irene: (44:13)

You can see information about the Black settlements, some of the underground railroad operatives and the leaders in the abolitionists community. Take kids down there and learn about that. There certainly is a Black history component at a museum Windsor at the Tim Chuck Museum that you can go and learn about. I know that the Bobby Harris components of Windsor’s community museum Windsor is working on developing an exhibit or a part of an exhibit that at least addresses the fact that there were enslaved people living on that property, working for the Bobbys for years so I’m glad that that’s taking place. There’s certainly Sandwich First Baptist Church which is a wonderful place to visit and they offer tours in non-pandemic times. That is a building that’s literally been there since 1851. It was built by the formerly enslaved people.

Irene: (45:06)

They literally made the bricks themselves after work. Every family had a certain quota. They either had to pay for bricks or make the bricks. They made it with the Detroit River clay and the river water. It’s just such a sacred place. Even if you’re not a Baptist, you just can’t go there and not feel something being inside that place or even just standing outside. It’s also a national historic site. There’s certainly First Baptist church in Puce. There’s first Baptist church in Amherstburg. These are national historic sites as well dating from the underground railroad era. There is incredible amounts of history in some of the burial places, believe it or not. If you’re driving down Bandwell Road towards County Road 42, there’s that incredible space where the baseline, Bandwell road, Black settlements used to be. All that remains are some graves that you look at those graves and it’s like, “Wow, look at this.”

Irene: (46:06)

People that were born in slavery who died here as free people. Certainly, there’s the Puce Black heritage burial site that you can visit. There are all of these places and I definitely recommend heading up to Chatham-Kent as well and just seeing some of their amazing resources. Not just uncle Tom’s cabin in the Buxton national historic site but I would also highly recommend the Chatham Black History Society which is also known as the Black Mecca Museum. It’s also an incredible place to visit. So much information and so well presented. Even the BME Freedom Park on the space that the BME Church, British Methodist Episcopal church in Chatham used to occupy there on King Street. Is it King Street? I forget.

Irene: (46:56)

Anyway, across the street from the Chatham Kent Black Historical Society, there is the amazing BME Freedom Park which features the beautiful sculpture of Mary Ann Shadd Cary that was actually made by Artis Shreve Lave who was also a Shadd descendant. You may have seen Artis Shreve Lane in the news lately. She’s in her 90s now. She was born in Buxton. She lived in Detroit and then in California for a long time but she’s one of the most eminent African-American sculptors. Currently, if you look at Joe Biden in his oval office, over his shoulder is her sculpture of Rosa Parks. Pretty impressive. She’s a great Black history story too. She’s still with us, thank heavens, but my goodness, her sculpture of Sojourner Truth is also in the Capitol rotunda. She’s done incredible work over the years and is just such a great story.

Dianne: (47:54)

I love it.

Dee: (47:55)

I love having these places because you can teach these things in schools but to actually have places where we can visit, have the kids go out to these actual places where it’s so different. I remember, like I said earlier, hearing for my grandparents and parents and having such a strong family story but when I started working at the museum, that’s when I was able to connect the dots and it was like, “Oh, this actually did happen.” I had the proof there just to connect the stories and it just makes it so much more real and interesting.

Irene: (48:29)

Sure. I mean, it’s not so visually interesting just to look at plaques but I want to mention a few of those too. If you take the kids in the car and stop every now and then and show them a plaque and explain what it’s about, it gives them a sense at least that they are part of this landscape, right? There is the amazing Ontario Heritage Trust Plaque to the Catholic Colored Mission of Windsor that you can find next to St. Alphonsus Church at [inaudible 00:48:55] park. That’s an amazing story. Do you guys know that story?

Dianne: (48:59)

No.

Irene: (48:59)

The Catholic colored mission of Windsor was established by the people at St. Alphonsus in the 19th century not to address underground railroad travelers because it was a little later than that era, but to address their kids. Those whose parents had fallen ill or could not take care of them for whatever reason we’re part of this mission. It was basically like an orphanage plus a soup kitchen plus a school. What’s really cool about that story aside from just the kindness that was shown and getting kids on their feet and giving them an education, the Father, the priest, Dean Wagner, who created that orphanage/mission/school, asked some nuns from Montreal to come down and help with it because they were really good at that sort of thing, The Sisters of St. Joseph.

Irene: (49:46)

They got here and they did help out with the Catholic colored mission but they also took a look around and said, “You guys don’t have a hospital in this town. Why is that?” People that were really sick had to be taken across on the ferry to Detroit to be treated. They established Hotel Dieu Hospital on the basis of having been invited here to work with this mission. That’s how we got a hospital in this town. If you go further down on McDougall between university and park, you’ll see a municipal plaque that’s about the Black community that used to exist in that McDougall Street corridor. There’s a plaque there about Mary Ann Shadd Cary. There’s information about James Llewellyn done. There’s information about the Walker House which was the Black hotel on that street.

Irene: (50:31)

If you go further up to McDougall and Wyandotte, there’s the wonderful reaching out mural, which you can use to teach kids about Black history. Teaching them about all of the people on that mural. That’s a great way to learn. There are just all these opportunities. Of course, Henry and Mary Bibbs’ plaque is over next to Mackenzie Hall on Sandwich Street. There’s the amazing set of murals in Patterson Park. You can use that as an opportunity in the open air, physically distanced or whatever, to teach your kids about every one of the people on that mural. There’s a lot going on and there’s a lot that is available to teach kids other than from a book.

Dianne: (51:11)

Exactly. I love that. I’m so inspired. I can’t even tell you. Dee, I’m a little bit jealous or could I be a lot jealous, that this is your direct history? You know what I mean? You are directly tethered to this. I do a lot of anti-racism work in America of all places and I’m always like, “I’m coming here as a Canadian. I know I look like an African-American but I’m not. This is heritage.” I’m always talking about these things and I feel so empowered now knowing about the history of where I am. I often say when I’m talking about this, our impact is global. Most of us and a lot of us are directly linked to the Transatlantic slave trade so we are connected and we are related.

Dianne: (52:04)

Because at the time of slavery, it wasn’t like families went together. It wasn’t like people who were stealing us from our land were like, “Oh, are you a family? Okay, all of you go on this ship. Was that your mom? You get to stay with her on this ship.” Our culture and our ethnicity was dependent on where the slave ship dropped you off. Whether it was in the Southern United States, or in Europe, or in the West Indies, our families were split up. I often tell African-Americans, “If you were to trace your DNA, I am sure you have Canadian heritage.” I tell Caribbean Canadians or people from the Caribbean, “If we trace our DNA, I’m sure you have roots here because they split our families up.”

Dianne: (52:48)

We are more connected than we know and we need to stop with the division like, “You’re Caribbean and you’re African-American.” That’s important. Absolutely. We are tribal people and that’s important, but know that we are all interconnected in this history. I think it’s important to acknowledge that when we’re talking to each other. Just because your family landed in South Carolina in 1622 doesn’t mean that you don’t have roots in Barbados, or Jamaica, or Trinidad, or Canada, or anywhere in Europe, right? It doesn’t mean that you’re not connected all of those stories.

Irene: (53:26)

Absolutely. Part of the problem that causes that psychology of division is that even when Black history is taught, it’s often taught from slavery forward. That’s beginning with chapter nine. We have to look at the historythat is preceding the transatlantic slave trade and understand these African cultures and all of the accomplishments of those various empires and kingdoms and communities. Realize too how even when their lives were so devastated and interrupted and disrupted destroyed in some ways by slavery, people still retained elements of that African culture and it does bring all of these cultures together.

Irene: (54:14)

We look at people coming over into America, for example and finding a way to replicate the instruments that they were used to from Africa, which results in the creation of the banjo using American materials. Things of that nature. The rhythms that survived. The certain linguistic elements that survived and just ideas about kinship and matrilineal cultures and so on. We have a lot to learn about the pre slave trade history too, and certainly, it’s our hope that that’s included in the curriculum when these changes are made.

Dianne: (54:54)

But we can start doing this stuff now at home. I love that Dee brought that up. How do we start to educate our own children so we can continue the conversation forward that they can tell their children about their rich history? Like I say, every time February rolls around, I am so empowered and I’m so thrilled and I’m so excited to hear about the accomplishments of my people, of our people, that are always overlooked. Like I said in the beginning, that there’s no place in the world that we have not touched or we have not been a part of. I think it’s really important to acknowledge that so that young people of African descent who are coming up today can feel powerful in their sense of identity. I find sometimes because we live in a White supremacist society, we’re always told we’re not good at enough or whatever it is that White supremacy likes to teach us to keep us divided and oppress, that we can break out of that understanding and know that we are powerful people in spite of all of these things.

Irene: (56:02)

Absolutely. Remember that representation matters too. Decolonize your bookshelf. Make sure that kids have books that have characters that look like them, they have some nonfiction children’s books that are about African or Black heritage, or Caribbean heritage. Make sure that you’re doing that. In so doing, you’re supporting Black authors and content creators and illustrators too, which is a beautiful thing to do.

Dee: (56:26)

Absolutely.

Dianne: (56:29)

I want to be of course, respectful of your time. Dee, do you have anything else for Irene?

Dee: (56:34)

Thank you so much, Irene. Maybe we can do a tour together.

Irene: (56:42)

Take the podcast on the road.

Dee: (56:48)

I want to get in the car with Irene.

Dianne: (56:48)

Yeah, exactly. 100%. Irene, youhave a book coming out soon. Where can we find you? How can we connect with you? How can we learn more about your work?

Irene: (56:56)

Please believe that when my book is ready everyone will know.

Dianne: (57:03)

Fair enough. [crosstalk 00:57:03].

Irene: (57:03)

I’m very excited that the light is at the end of the tunnel.

Dianne: (57:11)

I get that. I get that. Thank you so much for joining us today on the Two Black Girls Talk About Everything Podcast. It has been our absolute honor to host you and we are so appreciative of all the work that you do and the way that you bring to light our collective history.

Irene: (57:27)

Thank you for having me. Happy Black History Month.

Dee: (57:30)

Happy Black History Month.

Dianne: (57:31)

Dee and I want to extend our sincere gratitude to Irene Moore Davis for sharing her knowledge and her passion for Black Canadian history. We learned so much on this podcast and we really learned how we could start to educate ourselves and our children, and we will be forever grateful for that knowledge and that opportunity. Thank you so much. Thank you once again for listening to the podcast, Two Black Girls Talk About Everything. You can reach us at prospective social media pages. I am diannebondyofficial on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Tik Tok, all the places, and you can reach Dee at yogidee on Instagram and divineintentions on Instagram as well. You can also catch me at my website, diannebondyyoga.com and Dee on her website at deevineintentions.com. Thank you for listening and make sure that you go on Apple podcasts to rate, leave a comment and share because it really does help. We’ll see you next time. inaudible].

The Benefits of a Hands-Free Yoga Practice

The Benefits of a Hands-Free Yoga Practice

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.